Portable oxygen concentrators (POCs) are devices developed in response to demand for a lightweight, portable source of supplemental oxygen.[1] Pulse dose delivery allows concentrators to deliver medical grade oxygen all day, every day while remaining convenient to carry. Is Pulse Dose a More Efficient Form of Oxygen Delivery? To understand the mechanics of pulse dose […]

View ArticleInogen Oxygen Education Blog

What To Do With Your Oxygen Concentrator Parts When They’re No Longer Needed

If you use an oxygen concentrator, you will need to periodically replace some parts. Those parts need to be disposed of correctly or recycled when possible, so don’t throw them in the garbage. If you are finished with your oxygen concentrator, full units can often be donated. Let’s take a look at how to responsibly […]

View ArticlePulse Oximetry & Oxygen Saturation: What Oxygen Therapy Users Need to Know

A pulse oximeter is a handy medical device that uses two frequencies of light – red and infrared – to determine the percentage of hemoglobin in the blood that is saturated with oxygen, otherwise known as your oxygen saturation level (O2 sat level).[1] If you have ever been in a doctor’s office and heard your […]

View Article- Leader, “Understanding Oxygen Saturation.” Verywell Health, About, Inc., 7 May 2020, www.verywellhealth.com/oxygen-saturation-914796.

The Trouble with Mouth Breathing and Treatment Options

Wondering why mouth breathing matters, how it affects you and how to stop mouth breathing? If you are a mouth breather, you probably have all of these questions and more. Read on to learn why being a mouth breather can have a surprising impact on your health. Nose Breathing vs. Mouth Breathing You might not […]

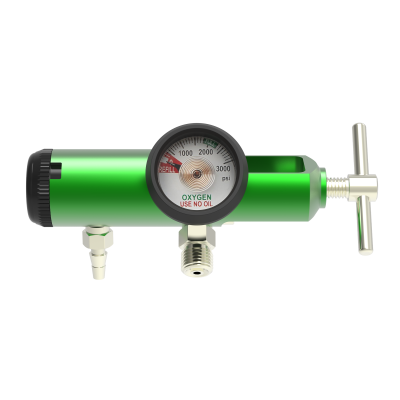

View Article10 Tips for Oxygen Safety in the Home

Home oxygen safety is one of the most important aspects of oxygen therapy, whether you choose an oxygen concentrator, oxygen cylinders or a liquid oxygen system as your oxygen supply source. Although oxygen is a safe, non-flammable gas, it does support combustion,[1] meaning things burn more readily and ignite easier in its presence.[2] As such, you […]

View ArticleAcute vs. Chronic Bronchitis: Understanding the Differences

Bronchitis is a respiratory illness that causes inflammation of the tubes that carry air to the lungs—also known as the airways or bronchial tubes. When the airways become irritated, swollen and inflamed, less air is able to travel to and from the lungs and mucus begins to form in them. This generally causes an irritating cough […]

View Article- WebMD. Understanding Bronchitis – the Basics. Reviewed at May 7, 2013. Bronchitis (Acute and Chronic): Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment (webmd.com)

Oxygen Concentrator vs. Nebulizer Machine

Many people with COPD and other respiratory diseases or illnesses have to use both oxygen concentrators and nebulizers in the management of their disease. However, if these medical devices have been prescribed to you for the first time, you might not understand the difference between the two. Learn the difference between an oxygen concentrator and […]

View ArticleOxygen Saturation: Normal Oxygen Level & Shortness of Breath

One of the most frequently asked questions about lung disease is also one of the most baffling: Why do people with COPD experience shortness of breath despite a normal oxygen level reading? What is normal oxygen saturation? Low oxygen saturation and a higher heart rate are common in COPD patients, so why would a person […]

View ArticleHoliday Travel Tips

When you have COPD, or any other lung disease requiring supplemental oxygen, preparing for holiday travel is a little different. We are here to help make your travel as easy as possible this season. Planning Your Holiday Travel Traveling for the holidays can be joyful and exciting or, if you have a lung disease like […]

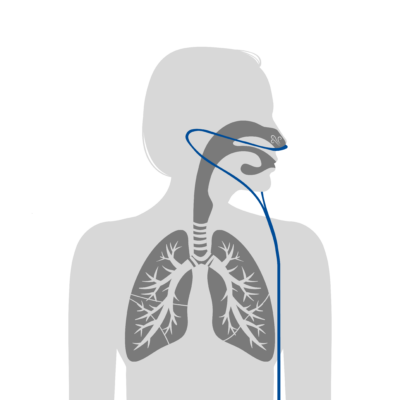

View ArticleTips for Increasing Nasal Cannula Comfort

For most oxygen therapy patients, learning how to use a nasal cannula as comfortably as possible is an important step in easily incorporating oxygen therapy into their lives. But for many people, figuring out how to wear the oxygen nose piece properly and learning what to do with all the tubing can be confusing. If […]

View ArticleHow to Exercise with an O2 Concentrator

Many people with breathing difficulties learn about the benefits of exercise after seeing their doctor or beginning pulmonary rehabilitation. Exercise gets your heart pumping and increases your breathing rate, which means increased circulation of oxygenated blood throughout the body. This can help your body with oxygenation of the tissues and, the better shape your muscles […]

View Article5 Steps to Qualifying for Home Oxygen Therapy

If you think you have a health condition that would benefit from oxygen therapy and you are interested in getting oxygen at home, talk to your doctor about whether you meet the criteria for oxygen therapy. Ask about options for supplemental oxygen for home use, about home O2 requirements and anything else you need to […]

View Article